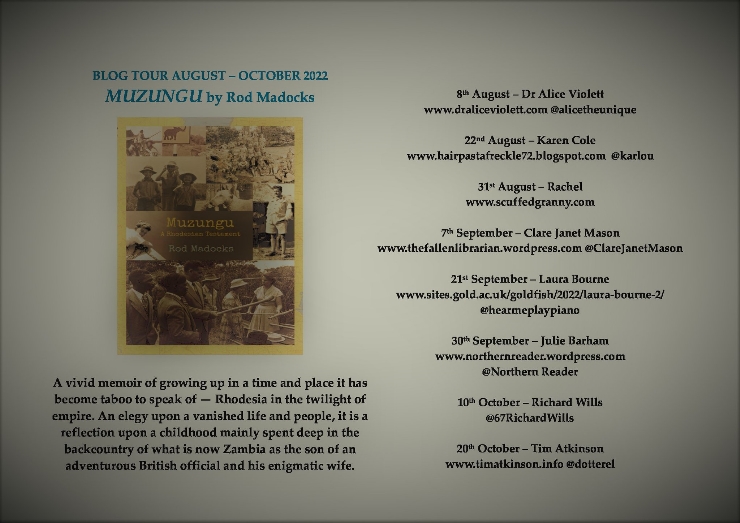

Blog tour: Muzungu by Rod Madocks

This post is part of a blog tour organised by Dogberry Books. I received a free copy of the book in return for an honest review.

‘Muzungu is a vivid memoir of growing up in a time and place it has become taboo to speak of — Rhodesia in the twilight of empire.

‘An elegy upon a vanished life and people, it is a reflection upon a childhood mainly spent deep in the backcountry of what is now Zambia as the son of an adventurous British official and his enigmatic wife.

‘It is a story of being raised by and among Black Africans, the best of whom are the people you admire most in the world, only to be shipped off to boarding school in England.

‘Muzungu, slang for a white person across swathes of Africa, is said to mean ‘a wanderer’ who strays over the land without purpose, or one who ‘spins around’ as if bewildered.

‘This poetic memoir charts a struggle to transcend that condition and find one’s own way at last through writing.’

Muzungu, by Rod Madocks, is an autobiography that by turns fascinates and entertains, and shocks and challenges.

It centres on his childhood in the last days of colonial Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and the influence of this on the rest of his life: his teenage years at a British boarding school, his itinerant young adulthood, the various jobs he did as an adult, and where he finds himself today, entering his eighth decade.

While Madocks frequently refers to his lack of a plan, direction and, at times, purpose (and his parents’ concern and disappointment about it), it’s this that, in the end, makes his memoir so interesting.

Muzungu is stuffed with stories and anecdotes from the many places Madocks has lived, learned, worked, and dossed over his lifetime. Some are shocking, some are humorous, many contain shades of both, but if there’s one constant, it’s that Muzungu is never boring.

What’s more, Madocks didn’t assume his profession as an author until later in life, but, as he points out, he was a writer all along. In the years before his first novel was published, he was practising the craft by diligently keeping journals, as well as accumulating the knowledge and experiences that inform his work.

Not only has this paid off in the form of a well-written and thoughtful autobiography, but it made me feel reassured that it’s not too late (and possibly even too early) for me to become a writer!

Madocks’ portrayal of his life in Northern Rhodesia, from his birth in 1952, until 1964 when it became independent and his family relocated to Britain, challenged some of my assumptions about what life was like for British officials and their kin living in the colonies at this time.

This was that all colonists lived in luxury, and as separately from Black Africans as possible, clung on to their European ways at all costs, and were explicitly and continually cruel to those whose countries they’d taken over, against a background of constant tension and bubbling dissent. Muzungu reminded me that there was no definitive “colonial experience”, as circumstances could differ so much between locations.

Madocks claims that it was a sense of adventure and hope, and a belief that they could make a positive difference, that motivated his parents to emigrate. Both of them lost their own parents young and were marked by trauma; his father by his experiences in the Second World War, his mother for reasons she refused to divulge for much of her life. Later on, he cared for both of them in their final years, and his account of this is really moving.

As he was born in the Protectorate, Madocks (and his sister Susan) was a second-generation immigrant by accident of birth. Living, for the most part, in rural rather than urban areas, he recalls a degree of cultural assimilation as he played with Black children, admired a number of Black adults whom he describes at length, and adopted local practices and language.

He has never stopped ruing leaving Africa and its people at the age of 12, or the political unrest that made it impossible for it to be the same as he remembered, and never felt “at home” anywhere else.

Even so, he concedes that Black and white people lived separately for the most part, and that as he grew up, he became increasingly aware that most Black Africans lived in extreme poverty and were deferent to whites (not to mention, many of the Black people he describes were employees of his parents), making him feel shame even as a child.

Furthermore, Madocks was sent to a white boarding school in Southern Rhodesia - aka Zimbabwe - and this made him more cognisant of racial tensions, and the Black population’s lack of political power. He prides the white ruling class in the areas he lived in for visiting “far fewer cruelties” on Black people than they did in South Africa, or in places where the colonists originated from other parts of Europe, but “far fewer” is still at least “some”.

The aspect of Muzungu that really challenged me was Madocks’ repeated references to current ‘erstwhile intellectuals in the humanities and social sciences’’ view that colonialism was all bad, its personnel all villains, and that Cecil Rhodes should be ‘deleted from history’. As a lapsed historian, I naturally got a bit defensive! Madocks is, of course, entitled to voice his perceptions and opinions in his own memoir, and they certainly make for an active, rather than passive, reading experience. I’ve popped my responses at the end of this post for anyone who’s interested.

Anyway, there were other aspects of Muzungu that especially interested the liberal historian of childhood/the family who still lives within me. Having researched how people use different lenses (in my work, it was ideas about only-childhood) to interpret and communicate their life stories, it was really interesting to see the importance Madocks placed on growing up in Africa, and leaving it against his will, in defining his character and subsequent experiences.

One of those experiences was the horror that was attending a boys’ boarding school in the 1960s, with the attendant perverted and violent teachers, strict hierarchies and casual cruelties between the pupils, and total lack of comfort and compassion that I’ve read about as part of my own research. I really felt for him when he described the traumatic memory of his experience at the hands of one of the teachers that has arisen, unbidden, at intervals ever since.

One effect I’ve come across of sending children to boarding school from a young age (Madocks was sent to prep schools in Southern Rhodesia and Britain before leaving Africa for good) is trauma from suddenly being cut them off from their families, in the sense that they were severed from people who previously met many of their physical and emotional needs, and also that it wasn’t socially acceptable to express homesickness or even talk about mothers and/or sisters.

Something that struck me in Muzungu was how little Madocks said about his sister, Susan. What with being different genders, they seemed to inhabit largely separate worlds from the start: their mother was better-disposed towards girl children than boy children; Madocks’ adventures in the African bundu were either solitary or undertaken with other boys or men; and they went to different schools - it’s possible that Susan wasn’t even sent away from home at all.

Susan pops up now and then throughout the book, but seems to totally disappear by the end, and I did want to know what happened to her. I imagine it would also be very interesting to read her take on growing up in Africa, and how it did (or didn’t) shape the rest of her life! In any case, her shadowy presence just shows how having a sibling wasn’t a guarantee of companionship or a heavily involved relationship.

Muzungu is a raw and fascinating memoir that gave me a lot to think about.

-

Madocks does a good job of communicating nuance in his writing, while seeming not to recognise it in historians’ latest work. Are they actually writing everything off as bad? Or are they simply introducing previously-lacking acknowledgements of the costs and harms of colonisation, providing essential correctives to previously excessively positive views of the British Empire, and re-evaluating evidence based on new understandings of human experience - which has always been part of any historian’s job description?

-

Nobody wants to “erase” figures like Rhodes. In fact, it’s important to educate people about them in a nuanced way, but having statues sends the message that we celebrate them and condone all their views and actions.

-

Madocks’ parents may have had pure intentions and a genuine goal of helping African people and setting them up to eventually rule themselves (not unproblematic by today’s standards, but not the worst), and he didn’t choose where he was born. That doesn’t change the original motivations behind colonisation, though: that white Europeans saw Black and brown people as naturally inferior “savages” in need of their “expert” help to become civilised; that they considered themselves entitled to just take land and power in Africa, Asia, and the Americas; and that they were in competition with other Europeans to have the biggest empire.

-

When discussing the legacy of Black slavery, Madocks uses other examples of slavery to show it’s something that people have always done to each other. Similarly to above, though, white Europeans justified enslaving Black Africans with their belief that Black people were naturally both “lesser” and “different” than them, and therefore deliberately designed by god to be their slaves. This differs from, for example, people capturing enemies as slaves in a war situation (still not a great thing to do, of course…).