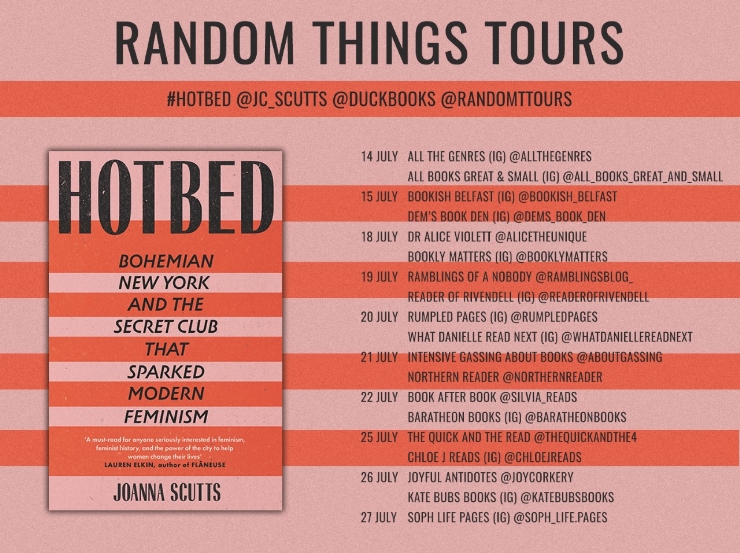

Blog tour: Hotbed by Joanna Scutts

This post is part of a blog tour organised by Random Things Blog Tours. I received a free copy of the book in return for an honest review.

‘New York City, 1912. The very idea of feminism is radical and outlandish, but a group of women believe they can change the world. They meet in a bustling Greenwich Village restaurant and give their club a name that enshrines the notion of difference of opinion: Heterodoxy.

‘Among themselves, the women could talk freely — no topic off limits — and plan their liberation without fear of a man labelling them difficult or strident. The group quickly grew: there were pairs of sisters and pairs of lovers; women entwined by family and marriage; and those who had studied together, worked together, and marched side by side for the vote.

‘However, the history of Heterodoxy remains elusive. To allow each other space to disagree, the women kept no records of their meetings. In Hotbed, Joanna Scutts unravels the never-before-told story of this secretive, unruly club by exploring the lives of its members.

‘Socialites and socialists; playwrights and scientists; actresses, activists and revolutionaries — these extraordinary, fervent women spearheaded the feminist movement and transformed an international feminist agenda into a modern way of life.’

In Hotbed, Joanna Scutts tells the stories of a selection of women who made a name for themselves as activists in New York in the 1910s, who were connected by their membership of an exclusive and lively discussion club, Heterodoxy, founded by trailblazing feminist Marie Jenney Howe.

I came to this book with little to no prior knowledge of Heterodoxy, any of its members, or women’s lives in New York/the US in the 1910s in general, so it was great to learn something new and hitherto unsuspected. It was a thrilling surprise to find, among Heterodoxy’s members, a number of divorced women, women who kept their surnames after marriage, and women who lived as couples, discreetly or otherwise.

At the time the club formed in 1912, Greenwich Village was a scruffy, bohemian enclave where radical middle-class men and women were more or less free to live as they liked. While Hotbed is a history of people, the neighbourhood comes across as a character in itself, crucial to the women’s personal development and successes. They occupy its homes; talk about big ideas and make big plans in its drawing rooms, cafes and restaurants; and use its public spaces as platforms from which to deliver their campaigns.

Heterodoxy’s members worked together on campaigns on a variety of hot topics, with individual women taking the lead on, or getting most involved with, whichever ones were closest to their hearts. We see them making the case for women’s suffrage; better working conditions and pay; reforms to race relations; marriage reform; education on and availability of birth control; pacifism; communism; and more.

I was especially interested to read about their campaign for the vote, being far more familiar with suffragettes’ and suffragists’ activities in Britain. I also paid particular attention to their views on limiting family size, and how they could help working-class women obtain information about, and access to, birth control, as this corresponded with my own work on family size in Britain during this period.

While this all sounds great, Scutts doesn’t shy away from the ways these women were very much ‘of their time’. They were mostly white and middle-class, and as a result, many of them didn’t understand how working-class and Black women faced multiple barriers, or had different goals to themselves. It’s an uncomfortable truth that while some members of Heterodoxy were simply ignorant but had their hearts in the right place, others were overtly racist.

But you do also see women making the effort to get among those they want to help and actually learning what life is like for them, and what they hope to gain. While the various displays put on by the more well-off and artistic members of Heterodoxy sounded very worthy and interesting, it was the women who had lived experience, or went out ‘on the ground’ - domestically and abroad - who particularly impressed me.

Historical time also plays its part in the club’s ultimate drift. The big cause that united virtually everyone in Heterodoxy was women’s suffrage; once that was achieved, there was nothing as unifying to take its place. Time also changed the character of Greenwich Village as it became a tourist hotspot (I kept thinking ‘I’d love to go back in time for a visit, but then I’d be a dreaded tourist!’), then succumbed to gentrification.

The First World War was a particularly big divider, as the women differed so much in what they thought their role in wartime should be: were they obligated to play a part in it as mothers, wives, sisters and US citizens, or should they oppose war as an outdated and incredibly male method of solving conflict? Following the war, differences in opinion on what women should be fighting for became even wider, especially in the light of the Red Scare, and a backlash against feminism from conservative women in the 1920s.

In the introduction, Scutts writes:

‘Friendship is an elusive subject for history, because we tend to take it for granted, to view it as something organic, unspoken, a connection that doesn’t require work or analysis… Biographers often treat friendship as subordinate to romantic or filial relationships, and less important than the influence of mentors and teachers in shaping a person’s life. But our friends have a profound influence on our work and our beliefs, on the way we live every day. For the women in this book, friendship was a bolstering, emboldening force.’

This is a message she reinforces throughout the book, by emphasising the living arrangements, collaboration, and assistance between the women of Heterodoxy.

Scutts gets closer to her subjects by examining not only their accounts of themselves, but what their friends said about them. We see them speak of one another with kindness and build each other up, without fawning or glossing over flaws or differences of opinion, and this helps Scutts build up her portraits of these women as admirable but imperfect, and therefore human.

Hotbed is an interesting and timely account of a group of remarkable women who were both of, and ahead of, their time.