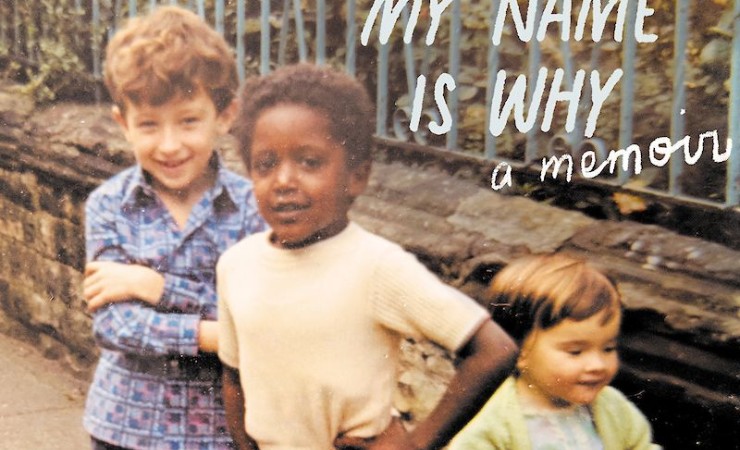

Review: My Name Is Why, by Lemn Sissay

My Name Is Why, by Lemn Sissay, is one of those books that is simultaneously easy and difficult to read. Easy, because his writing is very fluid, so I found myself speeding through it, but difficult because of all the heartbreaking injustices he experienced right from birth.

Combining official documents with personal recollections and commentary, Sissay takes us through his childhood, from being removed from his Ethiopian mother, to being brought up by a white foster family who sent him back into care at the age of 12, to living in a succession of decreasingly ‘homely’ children’s homes, the last of which was more like a prison.

Three particular aspects of Sissay’s experiences of growing up as black child in the British care system in the 1970s and 1980s struck me: racism (obviously), high standards of desired behaviour, and low standards of expected behaviour. For example, social services documents diminish his teacher’s reports that he is bright, popular and high-achieving by suggesting his teacher is over-praising him because of his race, and fail to acknowledge much of the racism he experiences in his day-to-day life.

We see how Sissay’s foster parents worried about the effect of his high achievements on their slightly younger natural son’s self-esteem, and increasingly viewed their rivalry and fights as a symptom that Sissay was delinquent, rather than normal brotherly behaviour. Eventually, they rejected him because he failed to live up to their religion-infused high standards, again by pushing boundaries in ways that many families would regard as a normal part of adolescence. This trend continued in the children’s homes, where staff punished children and moved them on to stricter accommodation for standard teenage behaviour that would be absorbed in most family environments. At the same time, they assumed the worst of their charges, being suspicious, for instance, when Sissay saved up to buy a guitar, suggesting that he got the money by less commendable means.

Sissay’s use of official documents is very effective in telling his story. Their release to him when he was 17 was pivotal. He learned so much that had previously been hidden from him, and they set the agenda for his adult life, so it feels important and right that he included them to such an extent. They also starkly lay out the attitudes of the British care system in the 1970s and 1980s; no-one could refute them. Sissay’s explanations of the real stories behind the reports, and how he felt when he first read them, make them all the more damning. That’s not to say it’s all completely bleak - there are individuals who criticise his foster parents’ abandonment, understand his situation and go above and beyond to help him.

I’ve had to grapple in the past with the issue of the inevitable ‘layering’ of subsequent adult thoughts over childhood experiences: that an autobiographer’s recollections of their childhood reflect how they feel about their childhood at the particular time of writing, and can never be an accurate account of how they felt as a child. You just have to accept that the author could have written a very different book at a different time in their life.

Sissay’s memoir is unlike others, though, in that he has a strong emotional memory of being forced to reassess his childhood experiences with the release of his files. While he could nonetheless have produced different accounts of his childhood depending on his age and situation, I can’t imagine many others will have had such a memorable experience of being made to reflect on their childhood, let alone at such a tender age. While it shouldn’t have happened that way - Sissay should have been kept with his birth mother, been aware of his and her name, not been treated as disposable by his foster family, and so on - it makes My Name Is Why all the more unusual and compelling as an autobiography.

With highly personal documents, emotional turmoil and honesty about the effects (particularly addiction and mental illness) of his turbulent childhood, it’s easy to forget that Sissay is nonetheless controlling the narrative by ending it at the age of 18, when he left the care system. If, like me, you’re only familiar with the headlines of his career, you’ll be left wondering what happened next. I guessed from the dedication (and had confirmed by good old Wikipedia) that he was eventually reunited with his birth mother and family; I don’t know whether he ever met, let alone made up with, his foster family as an adult, or how he got to where he is now. I did come away feeling a little dissatisfied in that respect - but Sissay’s flowing prose, vivid recollections and unusual method of telling his story more than made up for it.