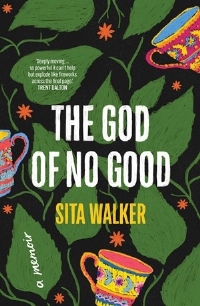

Blog tour: The God of No Good by Sita Walker

This post is part of a blog tour organised by Random Things Blog Tours. I received a free copy of the book in return for an honest review.

‘This is not a book about divorce. It’s not a book about God, either. You might think it is a book about goodness and what it means to be a good person, but it isn’t. Like everything else, this is about love.

‘Sita Walker was raised by five strong matriarchs who taught her to believe in God and to be good.

‘Her grandmother, mother and three aunts believe in their unshakeable Bahá’í faith, in the power of prayer, in sacrifice, in magic, in the healing of turmeric and tea, and the wisdom of dreams.

‘Now thirty-five, Sita finds herself at a loss – divorced, unable to remember the last time she prayed, and unsure if she is truly good at all.

‘Echoing the likes of Ocean Vuong, with more than a dash of Nora Ephron, readers witness Sita’s childhood and faith give way to new experiences – from falling in love again, searching for purpose and passion, and learning to lean on her community.’

In The God of No Good, by Sita Walker, the author presents a patchwork of episodes from her life and those of the women who shaped her: her mother, her grandmother, and her three aunts.

In doing so, she documents her experiences of gradually losing her faith, starting again at 35 after divorce, and the tragedies, successes, kindnesses, and wisdom of her maternal family.

I found The God of No Good a really interesting read. I especially enjoyed reading about the characters and lives of Sita’s grandmother Dolly, mother Fari, and aunts Irie, Mehri, and Mona at various ages, in India, Iran, and Australia.

While these five matriarchs have very distinct personalities and stories, what particularly struck me was the resourcefulness and wisdom shared by all of them, as well as the way they flock to support any of their number who is going through a difficult time.

Sita is very much a part of this support network, and it was so heart-warming to see how her mum and aunts cared for her after she split up with her ex-husband. Her female friends also come through with practical and emotional support.

When she’s in the thick of divorce, Sita feels like she’s disappointed her family, and doesn’t have coping skills on a par with those of her female relatives, but it becomes clear that they’ve also had times when they’ve felt broken and needed support. It’s just that they’ve long since come out the other side, and she has yet to do so.

Additionally, Sita tends to minimise her troubles because her mother, grandmother, and aunts have survived poverty, war, and the worst kinds of bereavement.

However, she’s grown up in a completely different time and place to them, so it doesn’t make sense to compare her pain to theirs and – as her relatives demonstrate through their words and actions – her feelings are absolutely valid.

On top of this, despite having the same parents and growing up in the same household, Sita had different experiences growing up to her own older siblings, partly because she’s so much younger than them (her brother Jamal calls her ‘an accident’; her father John calls her ‘a pleasant surprise’), and partly because her teenage sister Rahnee died when Sita was eight, altering the atmosphere and dynamics of her childhood home.

If the above paragraphs make this memoir sound miserable, please be assured that it really isn’t! There’s a lot of humour in Sita’s accounts of herself and her family, including some laugh-out-loud domestic scenes that made this book an unintentionally perfect follow-on from the book I read immediately before it – the hilarious Life Among the Savages, by Shirley Jackson.

Having studied memoirs pretty closely in my previous life as a historian, I also appreciated the author’s acknowledgement that the events she describes have filtered through memory (both hers and other people’s) and ‘my own poetic imagination’ (I can confirm this book is written beautifully).

I regard such filtering and creative presentation not only as unavoidable (all memories are interpretations, whether they’re written down for an audience or not) and essential if you want to produce a memoir that’s readable and engaging, but as one of the most interesting things about autobiography – what stories does the author consider most important? How do they mesh with their perception of themselves?

Sita’s necessarily pervasive point of view as someone who lacks faith in herself, and feels like she’s a disappointment who doesn’t live up to the achievements of the people she sees around her, was sadly all too relatable for me.

I was especially struck by a passage early on in the book, where Sita says she doesn’t feel like a writer because she’s only had a short story published, and opted for the security of a 9-5 profession (in her case, teaching) over the inherent precarity of work in the creative industries. I hope she now feels she can say ‘I am a writer’ with conviction.

The book’s non-chronological structure took a little getting used to and for the most part, I couldn’t discern what, if any, logic lay behind it, but it generally worked for me. Even so, I would have liked to have been able to refer to a family tree and a timeline showing when the family moved to each country.

The God of No Good is a warm, witty, and emotive celebration of a family of resourceful and wise women.