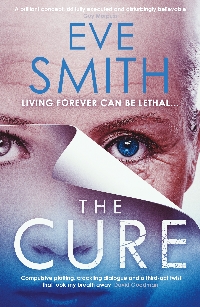

Blog tour: The Cure by Eve Smith

This post is part of a blog tour organised by Random Things Blog Tours. I received a free copy of the book in return for an honest review.

‘Living forever can be lethal…

‘Ruth is a law-abiding elder, working out her national service, but she has secrets. Her tireless research into the disease that killed her young daughter had an unexpected outcome: the discovery of a vaccine against old age. Just one jab a year reverses your biological clock, guaranteeing a long, healthy life.

‘But Ruth’s cure was hijacked by her colleague, Erik Grundleger, who hungers for immortality, and the SuperJuve – a premium upgrade – was created, driving human lifespan to a new high. The wealthy elite who take it were dubbed Supers, and the population began to skyrocket.

‘Then, a perilous side-effect of the SuperJuve emerged, with catastrophic consequences, and as the planet was threatened, the population rebelled, and laws were passed to restore order: life ends at 120. Supers are tracked down by Omnicide investigators like Mara, and executed.

‘Mara has her own reasons for hunting Supers, and she forms an unlikely alliance with Ruth to find Grundleger. But Grundleger has been working on something even more radical and is one step ahead, with a deadly surprise in store for them both…’

The Cure, by Eve Smith, asks: what if there was an injection that could protect people from age-related conditions, so they not only live longer, but stay physically healthy throughout their additional years?

Erstwhile scientist Ruth Sharp never set out to formulate a cure for mortality: the intervention she created was intended to treat progeria, the rapid-ageing disease that took away her daughter, Lettie, at the age of ten.

However, its anti-ageing effects got investors and less scrupulous scientists excited. The ReJuve, administered annually, became widely available, while the SuperJuve, developed by Ruth’s former colleague Erik Grundleger, was a one-and-done jab that promised immortality to those who could meet its exorbitant price tag – known as “Supers”.

Both vaccinations had consequences. In the case of the ReJuve, the population balance in the Global North got seriously out-of-whack, with increasing pressure for resources as well as diminished opportunities for the young, because older people kept their jobs for longer. The SuperJuve, meanwhile, turned out to significantly increase its takers’ risk of psychosis.

The solutions? Elders are required to spend their final years undertaking “national service” and jump through certain other hoops to qualify for their annual ReJuve, and are euthanised in their 121st year. The SuperJuve is banned, and it’s up to investigators like Mara Black to track down and execute remaining Supers, as well as anyone who might be cooking illicit SuperJuves.

When a letter from an old friend suggests to Ruth that Grundleger and other members of the team behind the SuperJuve – long-believed dead from a bombing by a religious sect who opposed them “playing God” – are not only alive, but secretly working on something that could take the banned treatment to unthinkable new levels, she contacts Mara, and the pair travel to the Caribbean to track them down – and hopefully put a stop to their activities once and for all.

The Cure is so gripping! As with her previous books, Smith has really thought through the wide-ranging, far-reaching consequences of the scientific development at the heart of the story – both immediately obvious ones, such as population changes, and more out-there ones, like unintended medical side-effects – and the measures taken to address them which, however well-meant by those in charge, give the novel its dystopian flavour.

For example, while the availability of the ReJuve means everyone in the UK has the opportunity to live and enjoy their lives for longer – which can only be a good thing, right? – it’s also ushered in state-sanctioned killing, however humanely it’s carried out.

When it comes to the Supers, admittedly, it is hard to see an alternative way of dealing with people who’ve undoubtedly committed terrible crimes and can’t possibly die of natural causes or (presumably) be rehabilitated. Even so, at the time they got the jab, they couldn’t have foreseen how it would change their characters for the worse, or that one day they could expect to be executed for having taken it.

The case of “normal” people facing compulsory euthanasia at 120 also messes with your head. By following Ruth, we see how elders are constantly reminded of their duty to die at that age, and monitored for signs of resistance to this.

We also see neighbours in Ruth’s co-housing complex put on brave faces as their mandated time approaches. Knowing when and how you’ll die may give you time to put your affairs in order and be present for the celebration of your life, but the whole thing nonetheless feels wrong. And that’s before you consider the fact that people can apply to “go early” if they feel they’ve had enough.

That’s not the only way older people are surveilled and controlled in The Cure, though. As mentioned above, they’re required to meet certain criteria to qualify for ReJuve boosters: having paid into a recognised pension for 60 years; eating the “right” foods, exercising frequently, and not taking recreational drugs (this is actively monitored); and “volunteering” for a public service scheme for the last two decades of their lives.

This raised the question: would I want to live a longer, healthier life if I had to spend a significant amount of that extra time being compelled to perform duties that have been chosen for me, and under constant scrutiny besides? For me, the appeal of a healthy retirement (a Millennial can but dream…) is having more time to pursue hobbies that I find enriching, and freedom from having to work at particular times for subsistence, having “done my time”.

To my mind, work as it’s popularly conceived doesn’t signal or confer moral character, and is far from the only way to contribute to society or live a “worthwhile” life – especially in the post-ageing world of The Cure, where the eradication of age-related diseases, as well as advances in automation, could mean there’s less work to do.

This valorisation of labour isn’t the only dystopic thing that’s carried over from our time. To name a few examples: the ReJuve is a patented, for-profit vaccine; it’s therefore far more widely available in high-income countries than in low-income ones, where it could make a truly revolutionary difference to quality of life; while the age of the Supers has largely passed, the odds still appear to be stacked against poor people and minorities, including those with disabilities unrelated to age; and we haven’t got a grip on climate change, with billions of people displaced due to frequent environmental disasters.

As well as being hooked by all the creative (if disturbing) details of life in a post-ageing society, the gear shift when Mara and Ruth suddenly found themselves in great danger had me on tenterhooks, and there’s a very exciting dramatic climax. What’s more, Mara learns something about herself that turns her world on its head.

The dynamic between the pair is also compelling, as Mara is quite a prickly character with personal reasons for hating the SuperJuve, and therefore little time for the woman who inadvertently got the ball rolling towards it. I couldn’t help but feel sorry for Ruth as her friendliness was continually rebuffed, and hope the two of them would eventually come to an understanding, however fragile.

The Cure is an inventive, gripping, and timely speculative thriller.