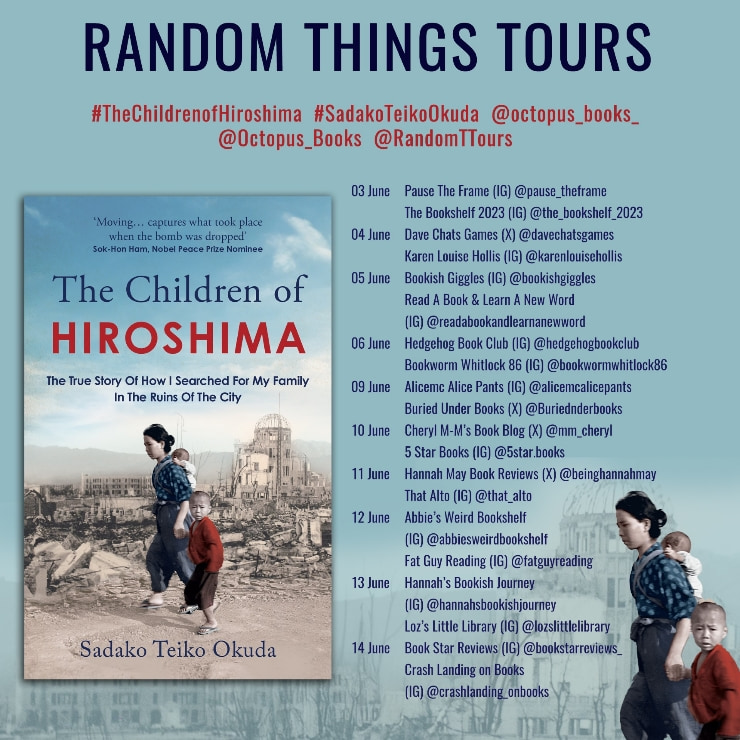

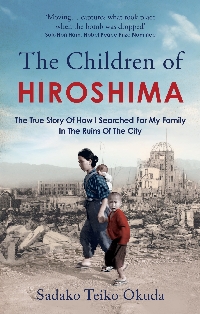

Blog tour: The Children of Hiroshima by Sadako Teiko Okuda

This post is part of a blog tour organised by Random Things Blog Tours. I received a free copy of the book in return for an honest review.

‘“The little boy did not cry or speak. He just stood there and stared at me intensely. With great effort I stood up and tested to see if I could walk with my injured foot. When I did, he came to stand even closer to me and, without saying a word, grabbed my little finger very tightly.”

‘Sadako Teiko Okuda was living in Osaki-shimo, an island off the mainland of Japan, when the bomb hit Hiroshima on the 6th of August 1945. There was a blinding flash and the window next to Sadako smashed, a shard of glass leaving a painful burn on her neck. Soon, news came that her niece and nephew who lived in Hiroshima were missing. There was only one thing she could do – leave the relative safety of the island and set off into the city to find them.

‘Over the following seven days Sadako roamed the ruins of the city, desperately searching for her family and coming across dozens of displaced children. With only water and a little medicine, she provided care, compassion and tenderness in the face of unprecedented tragedy. And in turn, they helped her to find hope in the very darkest of times.’

The Children of Hiroshima, by Sadako Teiko Okuda, takes the form of diary entries covering the period the author spent searching Hiroshima for her niece and nephew in the wake of the 1945 nuclear bombing, during which she helped several injured children.

These children were suffering from horrific burns, wounds, and radiation poisoning, and their parents and other family members had been killed by the blast, or were impossible to find amid the carnage and confusion. While Okuda was able to relieve their suffering a little, all of them soon succumbed to their injuries.

Rather than give in to despair, however, Okuda continued to help as many people as her strength allowed, and the experience bolstered her anti-war stance, which she conveys throughout.

What can I say about this book that hasn’t been said, down the years, by people of far greater standing than myself? The Children of Hiroshima isn’t a book you “enjoy”, but it’s essential reading that gives you a stark, no-holds-barred picture of the aftermath of a nuclear bombing.

The scenes and injuries Okuda depicts are like something out of a horror movie, but this really happened, at the hands of humans, just 80 years ago. In many of the cases she describes, it seems miraculous the grievously-wounded victims are still alive, and are just holding on to life for the time it takes for them to obtain aid for someone they love.

This is the vision of humanity Okuda returns to throughout the book: people, usually children, using their last moments to help their parents, siblings, or friends, even when they’re in unimaginable pain. Her over-arching message is that, unlike caring for others, war is not inherent to humanity and can be eradicated.

Okuda doesn’t play up her role in assisting people or paint herself as a heroine, instead coming across as endearingly modest, and even vulnerable. She recalls despair, when she wanted to give up looking for her young relatives and go back home to Osaki-shimo; beating herself up for not being able to save people, even though the severity of their injuries was such that nobody had that power; and moments of fear of, and anger and disgust at some of the survivors. She also experiences survivor’s guilt.

Of course, by its very nature, autobiography is curated and (consciously or otherwise) filtered to convey a particular narrative about events and the person describing them. Okuda put together the original Japanese edition of this book from scrappy, disordered diary notes in the 1970s, so in order to create a coherent account, we can reasonably assume she left out stories that were too similar to, or less detailed, illustrative, or striking than the ones she did include.

It’s also unavoidable that knowledge and wisdom Okuda gained subsequently would have altered her memories, and her interpretation of them – not that that detracts from their veracity. The emotions, admissions of weakness, and clarity of what Okuda stands for keep you turning the pages, and give this book far more power than, say, a dispassionate timeline of events.

Either side of Okuda’s narrative are remarks and short essays from relevant scholars, which pay tribute to her as a person and provide some medical and historical/social context for her recollections. These are mainly from the 2008 edition of the book, which this publication reproduces, but it does seem like a bit of a missed opportunity that these haven’t been added to/updated for 2025.

Not only do I expect we’ve learned some more about the long-term health impacts of the Hiroshima bombing in the past 17 years, but it would be interesting to read a sociologist/peace scholar’s take on Okuda’s story today, considering, for example, Israel’s targetting of children in Gaza, and that the Doomsday Clock is closer to midnight than it’s ever been.

Having been born in 1915, Okuda has almost certainly died by now, yet I can’t find any reference to her death online, which is quite surprising considering she was such a remarkable, respected woman. Then again, that might have been what she wanted: having lived an otherwise quiet, ordinary life as a home economics teacher, maybe she intended her contributions to the 2008 edition, at the age of 93, to be her closing remarks, and she didn’t want to risk her death overshadowing the premature, brutal ones she witnessed in 1945.

The Children of Hiroshima is a harrowing, vital read.