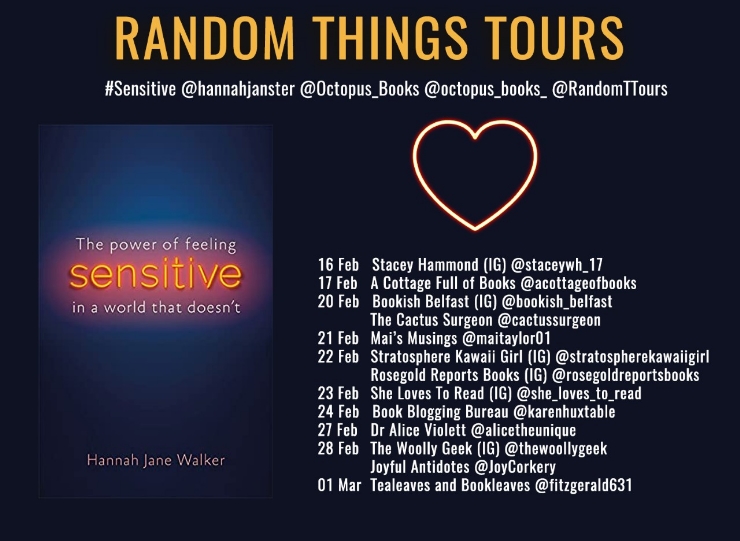

Blog tour: Sensitive: The hidden strength of sensitivity and empathy by Hannah Jane Walker

This post is part of a blog tour organised by Random Things Blog Tours. I received a free copy of the book in return for an honest review.

‘Hannah Jane Walker is a very sensitive person, along with at least a fifth of the population. Like many, she was conditioned to believe this was a weakness and a trait that she should try and overcome.

‘When she had her first child and realised that her little girl was sensitive too, Hannah decided to find out whether sensitivity might in fact be a positive trait. Her question led to some fascinating answers and ongoing research that suggests survival and thriving is not only limited to the fittest, but to the sensitive.

‘If you are someone, or know someone who sat at the edge of the party as a child, or waits to be sure about what you want to say only to never get a word in, or jumps at loud noises, or worries that you cry so easily at a beautiful piece of art, or that you just seem to feel so much (too much), this book reveals the strengths in these traits and also how we need to embrace them rather than be embarrassed by them.

‘People who are highly sensitive are highly caring, they are observant and notice new ways of doing things in difficult circumstances, they are able to follow their gut instincts (a real, scientific thing), they bring teams together, they listen well and are far more resilient than we’ve often been led to believe. The problem is that in today’s noisy world, they often suffer from lower self-esteem and confidence levels.’

In Sensitive, Hannah Jane Walker explores what it means to feel emotions keenly and be highly attuned to what’s going on around you, in a world that gives the biggest rewards to those who immediately jump in, shout the loudest, and make quick, confident decisions.

The more sensitive among us are given the message from a young age that there’s something wrong with us, and that we need to deny our true natures and “toughen up” if we’re going to get anywhere in life.

By examining her own experiences and talking to a selection of experts, Walker discovers that, while the trait of sensitivity hasn’t been given its due in recent times, it hasn’t necessarily always been undervalued, and could well be regarded as a valuable asset in the future - but in order to achieve that, we need to change the narrative.

As someone who’s very sensitive, I found myself going ‘yes, same here!’ a lot while reading about the author’s experiences, which felt very validating.

Can’t just “put up” with loud noises and strong smells like everyone else seems to be able to? Check.

Can’t think straight if there’s too much chat going on around me at once? Check.

Feel disturbed if there’s conflict or bad vibes between individuals in my environment, even if it’s nothing to do with me? Check.

Dwell for ages on criticisms, slights, and insults that most people seem to just shrug off? Check, check, check.

By interviewing Prof Michael Pluess, Walker discovers that sensitivity is regarded as a scale, rather than a binary - which makes total sense, as I couldn’t relate to everything she described. I don’t share her high level of interoception (as long as my basic needs are met, I’m only really aware of my body if something hurts), and haven’t had anything like her more spooky, difficult-to-explain experiences.

Something else that made me punch the air while reading this book were the views of Walker and some of the experts she interviewed that the education system just isn’t set up for more sensitive children.

As someone who spent a whole term of primary school hoping to stay home sick because I was scared of a teacher who’d shouted at me; purposely avoided playgrounds, dining halls and common rooms because there was too much going on; dreaded groupwork because I was so conscious of the personalities and relationships in my form; and frequently got behind in food tech or science classes because I was so careful about following the instructions - absolutely!

I could also concur with Walker and her interviewees that more sensitive people end up in lower-paid jobs. This is not only because people who come across as confident, commanding, and relatively unshakeable are more likely to put themselves forward for, and attain, leadership positions, but because those who think and feel deeply are particularly likely to be attracted to jobs that involve caring for or nurturing others which are traditionally poorly-paid.

I did disagree, though, that science is a career that’s especially attractive to less sensitive individuals, as it can involve a lot of careful, patient observation. I also reckon that a fair proportion of people go into, for example, bio/medical science, animal science, and environmental science because they really care about people, animals, and the planet, rather than for adulation or material gain.

I imagine (or, at least, hope!) that there are more high-sensitivity types in science, than there are low-sensitivity types who work as carers, nurses or teachers because they like having power over other people, as opposed to helping them.

Other aspects of this book that stood out to me were the discussions of how being told you’re sensitive affects your self-esteem, as it makes you think you’re wrong to be the way you are; and the idea that we need to change the narrative by telling children it’s actually good to be sensitive, and shouting more about the benefits highly sensitive people bring to any setting.

These put me in mind of my PhD research, where I found that only children internalise the negative messages they are given about what it means to be an only child, and this can affect how they think and talk about themselves and their childhoods.

Furthermore, just as Sensitive aims to change how people think about sensitivity, some of the contemporary-ish books on only-childhood I read for my thesis critically examined stereotypes and put forward alternative, more positive ideas.

I was naturally fascinated by Walker’s interviews with experts about how sensitivity may have been considered a more desirable trait in the past, and how it’s valued and rewarded in different societies and cultures. However, I do think that having a past-present-future (or present-past-future) structure to the book might have made this information more cohesive and impactful, and avoided some repetition and jumping back and forth.

I’d have also liked to have seen some consideration of intersectionality - for example, are highly sensitive Black people perceived and treated differently from highly sensitive white people? Can girls and women “get away” with showing they’re highly sensitive in a way that boys and men can’t?

Sensitive is interesting and validating, and gave me a lot to think about.